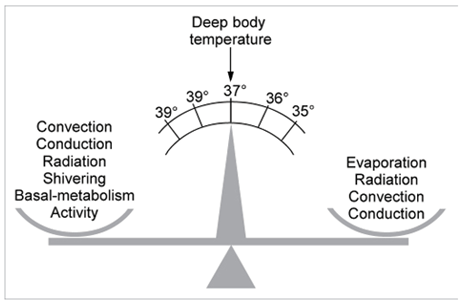

Humans are comfortable only within a very narrow range of conditions. Our body temperature is about 37°C, despite the fact that the body generates heat even while at rest: we must lose heat at the same rate it is produced and gain heat at the same rate it is lost. The diagram below shows the various ways by which our bodies achieve this.

The main factors influencing both physical and psychological human comfort are temperature, humidity, air movement, exposure to radiant heat sources and exposure to cool surfaces to radiate, or conduct to, for cooling.

Thermal simulation software can model with great accuracy the amount of heating or cooling energy required to achieve physiological comfort; it is unable to model highly variable human perceptions of comfort. Sound building envelope design based on modelling delivers an environment that addresses all the physical factors necessary for comfort (except humidity) but can’t always meet our psychological comfort needs.

Important triggers for psychological discomfort are radiation, air movement and conduction. Although they are less effective physiologically, they trigger innate self-preservation responses that override our ability to perceive physical comfort. Until they are met, we don’t feel thermally comfortable and our behaviour can render the best of design solutions ineffective. Acclimatisation is a critical component of psychological comfort.

Psychological thermal discomfort can make us set the thermostat on heating or cooling systems well beyond levels required for comfort. For every 1°C change in thermostat setting, it is estimated that our heating or cooling bill rises by around 10%. In other words, failure to address psychological comfort can increase heating and cooling energy use by up to 50% (Australian Greenhouse Office 2005).

Losing body heat

We lose heat in three ways: through evaporation, radiation and conduction.

Our most effective cooling method is the evaporation of perspiration. High humidity levels reduce evaporation rates. When relative humidity exceeds 60%, our ability to cool is greatly reduced. Evaporation rates are influenced by air movement. Generally, a breeze of 0.5 m per second provides a one-off comfort benefit equivalent to a 3°C temperature reduction.

We also lose heat by radiating to surfaces cooler than our body temperature, such as tiled concrete floors cooled by night breezes or earth coupling. The greater the temperature difference, the more we radiate. While not our main means of losing heat, radiation rates are very important to our psychological perception of comfort.

A third way to lose heat is conduction, i.e. through body contact with cooler surfaces such as when going for a swim or sleeping on an unheated waterbed. Conduction is most effective when we are inactive (e.g. sleeping) and is a particularly important component of psychological comfort.

Gaining body heat

When the heat produced by our bodies is insufficient to maintain body temperature, we shiver. This generates body heat and has a short-term physiological effect but also triggers our deepest psychological discomfort warning mechanisms. Our first response is generally to insulate ourselves by putting on more clothes and sheltering from wind and draughts. These actions are effective because we generate most of the heat we require from within, and reducing heat loss makes body heat more effective. Our minds quickly decide whether the adjustment is adequate for thermal comfort.

A secondary source of heat gain is radiation. As with cooling, radiation is very important to our perception of comfort. For example, we can feel cold in a room that is a comfortable 22°C if there is a cold window nearby; conversely, we can feel warm at 0°C if we are well insulated with warm clothing and standing in the sun.

The final source of heat gain is conduction. Simply holding someone’s hand can create psychological thermal comfort though a small amount of conduction. We conduct to cool floors and from heated floors. Heated floors also provide radiant heat and raise air temperatures through conduction and convection.